Family Is a Haven in a Heartless World

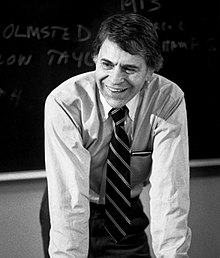

| Christopher Lasch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Built-in | Robert Christopher Lasch (1932-06-01)June 1, 1932 Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | February 14, 1994(1994-02-14) (aged 61) Pittsford, New York, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Nell Commager (m. 1956) |

| Bookish background | |

| Alma mater |

|

| Thesis | Revolution and Democracy[1] (1961) |

| Doctoral advisor | William Leuchtenburg[2] [three] |

| Influences |

|

| Academic work | |

| Subject field | History |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral students |

|

| Notable works | The Culture of Narcissism (1979) |

| Influenced |

|

Robert Christopher Lasch (June 1, 1932 – February xiv, 1994) was an American historian, moralist and social critic who was a history professor at the University of Rochester. He sought to use history every bit a tool to awaken American society to the pervasiveness with which major institutions, public and private, were eroding the competence and independence of families and communities. Lasch strove to create a historically informed social criticism that could teach Americans how to deal with rampant consumerism, proletarianization, and what he famously labeled "the culture of narcissism".

His books, including The New Radicalism in America (1965), Haven in a Heartless World (1977), The Culture of Narcissism (1979), The True and Only Sky (1991), and The Defection of the Elites and the Betrayal of Commonwealth (published posthumously in 1996) were widely discussed and reviewed. The Culture of Narcissism became a surprise all-time-seller and won the National Book Laurels in the category Current Involvement (paperback).[6] [a]

Lasch was ever a critic of mod liberalism and a historian of liberalism's discontents, but over time, his political perspective evolved dramatically. In the 1960s, he was a neo-Marxist and acerbic critic of Common cold War liberalism. During the 1970s, he supported certain aspects of cultural conservatism with a left-leaning critique of capitalism, and drew on Freud-influenced critical theory to diagnose the ongoing deterioration that he perceived in American culture and politics. His writings are sometimes denounced past feminists[7] and hailed by conservatives[8] for his apparent defence force of family unit life.

He eventually concluded that an ofttimes unspoken, but pervasive, faith in "Progress" tended to make Americans resistant to many of his arguments. In his last major works he explored this theme in depth, suggesting that Americans had much to larn from the suppressed and misunderstood populist and artisan movements of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[nine]

Biography [edit]

Born on June 1, 1932, in Omaha, Nebraska, Christopher Lasch came from a highly political family unit rooted in the left. His begetter, Robert Lasch, was a Rhodes Scholar and journalist who won a Pulitzer prize for editorials criticizing the Vietnam State of war while he was in St. Louis.[9] [x] His mother, Zora Lasch (née Schaupp), who held a philosophy doctorate, worked every bit a social worker and teacher.[11] [12] [thirteen]

Lasch was agile in the arts and letters early, publishing a neighborhood newspaper while in grade school, and writing the fully orchestrated "Rumpelstiltskin, Opera in D Major" at the age of 13.[9]

Career [edit]

Lasch studied at Harvard University, where he roomed with John Updike, and Columbia Academy, where he worked with William Leuchtenburg.[14] Richard Hofstadter was as well a significant influence. He contributed a Foreword to later editions of Hofstadter'south The American Political Tradition and an article on Hofstadter in the New York Review of Books in 1973. He taught at the University of Iowa and and so was a professor of history at the Academy of Rochester from 1970 until his death from cancer in 1994. Lasch also took a conspicuous public role. Russell Jacoby acknowledged this in writing that "I practice non recall any other historian of his generation moved equally forcefully into the public loonshit".[12] In 1986 he appeared on Channel iv television in give-and-take with Michael Ignatieff and Cornelius Castoriadis.[15]

During the 1960s, Lasch identified every bit a socialist, but one who establish influence not but in the writers of the time, such as C. Wright Mills, but besides in earlier contained voices, such as Dwight Macdonald.[16] Lasch became farther influenced by writers of the Frankfurt School and the early New Left Review and felt that "Marxism seemed indispensable to me".[17] During the 1970s, notwithstanding, he became disenchanted with the Left's belief in progress—a theme treated later past his student David Noble—and increasingly identified this belief as the factor that explained the Left's failure to thrive despite the widespread discontent and disharmonize of the times. He was a professor of history at Northwestern Academy from 1966 to 1970.[18]

At this signal Lasch began to formulate what would become his signature manner of social critique: a syncretic synthesis of Sigmund Freud and the strand of socially conservative thinking that remained deeply suspicious of commercialism and its furnishings on traditional institutions.

Besides Leuchtenburg, Hofstadter, and Freud, Lasch was especially influenced by Orestes Brownson, Henry George, Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Philip Rieff.[xix] A notable group of graduate students worked with Lasch at the University of Rochester, Eugene Genovese, and, for a time, Herbert Gutman, including Leon Fink, Russell Jacoby, Bruce Levine, David Noble, Maurice Isserman, William Leach, Rochelle Gurstein, Kevin Mattson, and Catherine Tumber.[xx]

Personal [edit]

Lasch married Nellie Commager, girl of historian [Henry Steele Commager], in 1956.[21] They had 4 children: Robert, Elizabeth, Catherine, and Christopher.[22]

Decease [edit]

After seemingly successful cancer surgery in 1992, Lasch was diagnosed with metastatic cancer in 1993. Upon learning that it was unlikely to significantly prolong his life, he refused chemotherapy, observing that it would rob him of the free energy he needed to keep writing and education. To one persistent specialist, he wrote: "I despise the cowardly clinging to life, purely for the sake of life, that seems so deeply ingrained in the American temperament."[9] Lasch succumbed to his cancer at his Pittsford, New York, home on February 14, 1994, at age 61.[23]

Ideas [edit]

The New Radicalism in America [edit]

Lasch'southward earliest argument, predictable partly by Hofstadter'south concern with the cycles of fragmentation among radical movements in the United States, was that American radicalism had at some point in the past get socially untenable. Members of "the Left" had abandoned their former commitments to economic justice and suspicion of power, to assume professionalized roles and to support commoditized lifestyles which hollowed out communities' self-sustaining ethics. His first major book, The New Radicalism in America: The Intellectual as a Social Type, published in 1965 (with a promotional blurb from Hofstadter), expressed those ideas in the form of a bracing critique of twentieth-century liberalism'due south efforts to accumulate power and restructure social club, while declining to follow upwardly on the promise of the New Deal.[24] About of his books, fifty-fifty the more strictly historical ones, include such sharp criticism of the priorities of alleged "radicals" who represented merely extreme formations of a rapacious capitalist ethos.

His bones thesis nigh the family, which he first expressed in 1965 and explored for the residual of his career, was:

When government was centralized and politics became national in scope, equally they had to be to cope with the energies let loose by industrialism, and when public life became faceless and bearding and society an baggy democratic mass, the old organisation of paternalism (in the home and out of it) collapsed, fifty-fifty when its semblance survived intact. The patriarch, though he might withal preside in splendor at the head of his board, had come up to resemble an emissary from a government which had been silently overthrown. The mere theoretical recognition of his authorisation by his family could not alter the fact that the authorities which was the source of all his ambassadorial powers had ceased to exist.[25]

The Culture of Narcissism [edit]

Lasch'due south most famous work, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (1979), sought to relate the hegemony of modern-24-hour interval capitalism to an inroad of a "therapeutic" mindset into social and family life similar to that already theorized by Philip Rieff. Lasch posited that social developments in the 20th century (e.m., World War II and the rise of consumer civilisation in the years following) gave rise to a narcissistic personality construction, in which individuals' fragile cocky-concepts had led, among other things, to a fear of commitment and lasting relationships (including religion), a dread of crumbling (i.due east., the 1960s and 1970s "youth culture") and a boundless admiration for fame and celebrity (nurtured initially by the movement moving-picture show manufacture and furthered principally by television). He claimed, farther, that this personality type conformed to structural changes in the world of work (e.g., the decline of agriculture and manufacturing in the USA and the emergence of the "information historic period"). With those developments, he charged, inevitably there arose a certain therapeutic sensibility (and thus dependence) that, inadvertently or not, undermined older notions of self-help and individual initiative. By the 1970s, even pleas for "individualism" were desperate and essentially ineffectual cries that expressed a deeper lack of meaningful individuality.

The True and Only Heaven [edit]

Almost explicitly in The Truthful and Only Heaven, Lasch developed a critique of social modify among the heart classes in the U.s., explaining and seeking to counteract the autumn of elements of "populism". He sought to rehabilitate this populist or producerist alternative tradition: "The tradition I am talking most ... tends to exist skeptical of programs for the wholesale redemption of society ... It is very radically democratic and in that sense information technology clearly belongs on the Left. Simply on the other hand information technology has a good deal more respect for tradition than is mutual on the Left, and for faith too."[26] And said that: "...any movement that offers whatsoever existent promise for the future will have to find much of its moral inspiration in the plebeian radicalism of the past and more by and large in the indictment of progress, large-calibration production and bureaucracy that was drawn up past a long line of moralists whose perceptions were shaped by the producers' view of the world."[27]

Critique of progressivism and libertarianism [edit]

By the 1980s, Lasch had poured scorn on the whole spectrum of contemporary mainstream American political thought, angering liberals with attacks on progressivism and feminism. He wrote that

A feminist movement that respected the achievements of women in the past would not disparage housework, motherhood or unpaid civic and neighborly services. It would not make a paycheck the only symbol of achievement. ... It would insist that people need self-respecting honorable callings, not glamorous careers that carry high salaries only take them away from their families.[28]

Journalist Susan Faludi dubbed him explicitly anti-feminist for his criticism of the abortion rights movement and opposition to divorce.[29] But Lasch viewed Ronald Reagan's conservatism as the antithesis of tradition and moral responsibility. Lasch was non generally sympathetic to the crusade of what was then known every bit the New Correct, particularly those elements of libertarianism most axiomatic in its platform; he detested the encroachment of the backer marketplace into all aspects of American life.

Lasch rejected the dominant political constellation that emerged in the wake of the New Deal in which economic centralization and social tolerance formed the foundations of American liberal ethics, while also rebuking the diametrically opposed constructed conservative credo fashioned by William F. Buckley Jr. and Russell Kirk. Lasch was also critical and at times dismissive toward his closest contemporary kin in social philosophy, communitarianism as elaborated by Amitai Etzioni. Only populism satisfied Lasch'southward criteria of economic justice (not necessarily equality, but minimizing form-based divergence), participatory democracy, potent social cohesion and moral rigor; withal populism had made major mistakes during the New Deal and increasingly been co-opted past its enemies and ignored by its friends. For instance, he praised the early work and thought of Martin Luther King Jr. equally exemplary of American populism; yet in Lasch's view, King fell short of this radical vision by embracing in the terminal few years of his life an essentially bureaucratic solution to ongoing racial stratification.

He explained in one of his books The Minimal Self,[30] "information technology goes without maxim that sexual equality in itself remains an eminently desirable objective ...". In Women and the Common Life,[31] Lasch clarified that urging women to abandon the household and forcing them into a position of economic dependence in the workplace, pointing out the importance of professional careers does not entail liberation, then long every bit these careers are governed by the requirements of corporate economy.

The Revolt of the Elites: And the Betrayal of Democracy [edit]

In his last months, he worked closely with his girl Elisabeth to consummate The Revolt of the Elites: And the Betrayal of Democracy, published in 1994, in which he "excoriated the new meritocratic course, a group that had achieved success through the up-mobility of teaching and career and that increasingly came to exist defined past rootlessness, cosmopolitanism, a thin sense of obligation, and diminishing reservoirs of patriotism," and "argued that this new grade 'retained many of the vices of elite without its virtues', lacking the sense of 'reciprocal obligation' that had been a feature of the old order."[32]

Christopher Lasch analyzes[33] the widening gap between the height and lesser of the social limerick in the U.s.. For him, our epoch is determined by a social miracle: the defection of the elites, in reference to The Revolt of the Masses (1929) of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset. According to Lasch, the new elites, i.e. those who are in the elevation 20 percent in terms of income, through globalization which allows total mobility of capital, no longer live in the same world equally their fellow-citizens. In this, they oppose the old bourgeoisie of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which was constrained by its spatial stability to a minimum of rooting and civic obligations.

Globalization, according to the historian, has turned elites into tourists in their ain countries. The de-nationalization of society tends to produce a class who run across themselves equally "world citizens, simply without accepting… any of the obligations that citizenship in a polity unremarkably implies". Their ties to an international culture of piece of work, leisure, information – make many of them securely indifferent to the prospect of national decline. Instead of financing public services and the public treasury, new elites are investing their money in improving their voluntary ghettos: private schools in their residential neighborhoods, private law, garbage collection systems. They have "withdrawn from common life".

Composed of those who control the international flows of capital and information, who preside over philanthropic foundations and institutions of higher didactics, they manage the instruments of cultural production and thus gear up the terms of public contend. Then, the political fence is limited mainly to the ascendant classes and political ideologies lose all contact with the concerns of the ordinary citizen. The result of this is that no one has a likely solution to these issues and that there are furious ideological battles on related issues. However, they remain protected from the issues affecting the working classes: the refuse of industrial activity, the resulting loss of employment, the decline of the middle course, increasing the number of the poor, the ascent crime rate, growing drug trafficking, the urban crunch.

In addition, he finalized his intentions for the essays to be included in Women and the Common Life: Love, Marriage, and Feminism, which was published, with his daughter's introduction, in 1997.

Selected works [edit]

Books [edit]

- 1962: The American Liberals and the Russian Revolution.

- 1965: The New Radicalism in America 1889-1963: The Intellectual Equally a Social Type.

- 1969: The Agony of the American Left.

- 1973: The World of Nations.

- 1977: Haven in a Heartless World: The Family unit Besieged.

- 1979: The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations.[6]

- 1984: The Minimal Self: Psychic Survival in Troubled Times.

- 1991: The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics.

- 1994: The Revolt of the Elites: And the Betrayal of Democracy, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 9780393313710

- 1997: Women and the Common Life: Love, Matrimony, and Feminism.

- 2002: Plain Mode: A Guide to Written English.

Manufactures [edit]

- Lasch, Christopher (August 1958). "The Anti-Imperialists, the Philippines, and the Inequality of Man". Journal of Southern History. 24 (3): 319–331. doi:x.2307/2954987. JSTOR 2954987.

- Lasch, Christopher (June 1962). "American Intervention in Siberia: A Reinterpretation". Political Scientific discipline Quarterly. 77 (2): 205–223. doi:10.2307/2145870. JSTOR 2145870.

- Lasch, Christopher (1965), "Introduction", in Lasch, Christopher (ed.), In The Social Idea of Jane Addams, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, pp. xiii–xxvii.

- "Divorce and the Family in America". The Atlantic. November 1966.

- Lasch, Christopher; Fredrickson, George M. (Dec 1967). "Resistance to Slavery". Ceremonious State of war History. 13 (4): 315–329. doi:x.1353/cwh.1967.0026.

- "Symposium: Prospects for American Radicalism". New Politics. March 1969.

- "Nativity, Death and Technology: The Limits of Cultural Laissez-Faire". The Hastings Eye Report. 2 (3). June 1972.

- "Achieving Parody". The Hastings Eye Report. 3 (1). February 1973.

- "Later on the Church building the Doctors, Afterward the Doctors Utopia". New York Times Volume Review. February 24, 1974.

- "The Suppression Of Clandestine Wedlock In England: The Union Act Of 1753". Salmagundi. 26. Leap 1974.

- "The Democratization of Culture: A Reappraisal". Alter. 7 (six). Summertime 1975. The Hereafter of the Humanities

- "The State of the Humanities: A Symposium". Change. 7. Summer 1975.

- "Psychiatry: Call It Teaching or Phone call It Treatment". The Hastings Center Report. five (three). August 1975.

- "The Family as a Haven in a Heartless Globe". Salmagundi. 35. Fall 1976.

- "The Waning of Individual Life". Salmagundi. 36. Winter 1977.

- "Recovering Reality". Salmagundi. 42. Summertime–Fall 1978. The Politics of Anti-Realism

- "Lewis Mumford and the Myth of the Machine". Salmagundi. 49. Summer 1980.

- "The Freudian Left and Cultural Revolution". New Left Review. New Left Review. I (129). September–Oct 1981.

- "The Modernist Myth of the Future". Revue Française d'Études Américaines. 16. Feb 1983.

- "The Life of Kennedy's Decease". Harper's Magazine. October 1983.

- "The Deposition of Work and the Apotheosis of Art". Harper's Mag. Feb 1984.

- "1984: Are We In that location?". Salmagundi. 65. Fall 1984.

- "The Politics of Nostalgia". Harper's Magazine. November 1984.

- "Historical Sociology and the Myth of Maturity". Theory and Society. 14 (v). September 1985.

- "A Typology of Intellectuals". Salmagundi. 70–71. Jump–Summer 1986. Intellectuals

- "A Typology of Intellectuals: Two. The Instance of C. Wright Mills". Salmagundi. seventy–71: 102–107. Jump–Summer 1986.

- "A Typology of Intellectuals: III Melanie Klein, Psychoanalysis, and The Revival of Public Philosophy". Salmagundi. 70–71. Spring–Summer 1986.

- "Traditional Values". Harper'southward Mag. September 1986.

- "The New Feminist Intellectual: A Discussion". Salmagundi. 70–71. Spring–Summer 1986. Intellectuals.

- "The Communitarian Critique of Liberalism". Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 69 (1–ii). Spring–Summertime 1986. Symposium: Habits of The Middle.

- "Fraternalist Manifesto". Harper's Mag. April 1987.

- "What's Incorrect with the Right?". Tikkun. I. 1987. Archived from the original on March 17, 2004.

- "Politics American Style". Salmagundi. 78–79. Spring–Summer 1988.

- "The Grade of '54, Thirty-V Years Afterwards". Salmagundi. 84. Autumn 1989.

- "Consensus: An Academic Question?". The Journal of American History. 76 (two). September 1989.

- "Counting past Tens". Salmagundi. 81. Winter 1989.

- "Conservatism Against Itself". First Things. Apr 1990.

- "Retentivity and Nostalgia, Gratitude and Pathos". Salmagundi. 85–86. Winter–Jump 1990.

- "Religious Contributions to Social Movements: Walter Rauschenbusch, the Social Gospel, and Its Critics". Journal of Religious Ethics. 18: 7–25. Spring 1990.

- "The Lost Art of Political Argument". Harper'southward Magazine. September 1990.

- "Bookish Pseudo-Radicalism: The Charade of "Subversion"". Salmagundi, 25th Anniversary Issue. 88–89. Autumn 1990.

- "Liberalism and Civic Virtue". Telos. New York. 88. Summer 1991.

- "The Fragility of Liberalism". Salmagundi. 92. Autumn 1991.

- "The Illusion of Disillusionment". Harper's Magazine. July 1991.

- "Gnosticism, Ancient and Modern: The Religion of the Future?". Salmagundi. 96. Fall 1992.

- "Communitarianism or Populism?". New Oxford Review. May 1992. Archived from the original on July xvi, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- Lasch, Christopher (August 10, 1992). "For Shame: Why Americans Should Be Wary of Self-Esteem". New Republic.

- "Hillary Clinton, Child Saver". Harper's Mag. October 1992.

- Lasch, Christopher (1993), "The Culture of Consumption", in Kupiec Cayton, Mary; Gorn, Elliott J.; Williams, Peter W. (eds.), Encyclopedia of American Social History, vol. 2 (of 3 vols), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 1381–1390.

- "The Culture of Poverty and the Culture of 'Compassion'". Salmagundi. 98–99. Leap–Summer 1993.

- Blake, Casey; Phelps, Christopher (March 1994). "History as Social Criticism: Conversations with Christopher Lasch". Journal of American History. 80 (4): 1310–1332. doi:10.2307/2080602. JSTOR 2080602. Interview.

- "The Revolt of the Elites: Have they Canceled their Fidelity to America?". Harper'due south Magazine. Nov 1994.

Meet also [edit]

- Cultural narcissism

- Rhetoric of therapy

Notes [edit]

- ^ From 1980 to 1983 in National Book Honour history there were dual awards for hardcover and paperback books in many categories. Most of the paperback accolade-winners were reprints, including this ane (September 1979), but its first edition (January 1979) was eligible in the same award twelvemonth.

References [edit]

- ^ Lasch, Christopher (1961). Revolution and Republic: The Russian Revolution and the Crunch of American Liberalism, 1917–1919 (PhD thesis). New York: Columbia University. OCLC 893274321.

- ^ Mattson, Kevin (2003). "The Historian as a Social Critic: Christopher Lasch and the Uses of History". The History Instructor. 36 (3): 378. doi:10.2307/1555694. ISSN 1945-2292. JSTOR 1555694.

- ^ a b c Mattson, Kevin (March 31, 2017). "An Oracle for Trump's America?". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Vol. 63, no. 30. Washington. ISSN 0009-5982. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Byers, Paula K., ed. (1998). "Christopher Lasch". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Vol. 9 (2d ed.). Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research. p. 213. ISBN978-0-7876-2549-8 . Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Mattson, Kevin (1998). Creating a Democratic Public: The Struggle for Urban Participatory Commonwealth During the Progressive Era 1st Edition. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Land University Printing. p. vii. ISBN978-0-271-01723-five.

- ^ a b "National Volume Awards – 1980". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-09.

There was a "Contemporary" or "Current" laurels category from 1972 to 1980. - ^ Hartman (2009)

- ^ Jeremy Beer, "On Christopher Lasch," Modern Historic period, Fall 2005, Vol. 47 Issue 4, pp 330-343

- ^ a b c d Miller (2010)

- ^ Dark-brown, David (August 1, 2009) Cold War Without End Archived February three, 2013, at annal.today, The American Bourgeois

- ^ Miller, Eric (April 16, 2010). Promise in a Scattering Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch. ISBN9780802817693.

- ^ a b Jacoby, Russell (1994). "Christopher Lasch (1932-1994)". Telos (97): 121–123. , p123

- ^ Beer, Jeremy (2005). "On Christopher Lasch" (PDF). Modern Age: 330–343.

- ^ Lasch, Christopher. Plain Style : A Guide to Written English language. Academy of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Voices: The Culture of Narcissism, Modernity and Its Discontents. Partial transcribed version available as: "Beating the Retreat into Private Life," The Listener, March 27, 1986: 20-21. http://world wide web.magmaweb.fr/spip/IMG/pdf_CC-Lasch-BBC.pdf Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Lasch, Christopher (1991). The True and Only Heaven: Progress and its Critics. Norton. p. 26. ISBN978-0-393-30795-five.

- ^ Lasch, Christopher (1991). The True and Only Heaven: Progress and its Critics. Norton. p. 29. ISBN978-0-393-30795-5.

- ^ Grimes, William. "Christopher Lasch is Expressionless at 61; Wrote about America'southward Malaise". New York Times. February. 15, 1994

- ^ Beer, (2005)

- ^ Misa, Thomas J. (April 2011). "David F. Noble, 22 July 1945 to 27 December 2010". Technology and Culture. 52 (2): 360–372. doi:10.1353/tech.2011.0061. S2CID 109911547.

- ^ [HISTORIAN: CHRISTOPHER LASCH | https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/historian-christopher-lasch/]

- ^ [Christopher Lasch, Renowned Social Critic, Dies | https://www.rochester.edu/news/prove.php?id=839]

- ^ Beer, Jeremy (March 27, 2006)The Radical Lasch, The American Bourgeois

- ^ David S. Brown, Beyond the Frontier: The Midwestern Vox in American Historical Writing (2009), 154

- ^ Lasch, The New Radicalism in America, 1889–1963 (1965) p 111

- ^ Brawer, Peggy; Sergio Benvenuto (1993). "An interview with Christopher Lasch". Telos. 1993 (97): 124–135. doi:10.3817/0993097124. S2CID 145693224. , p125

- ^ Lasch, Christopher (1991). "Liberalism and Borough Virtue". Telos. 1991 (88): 57–68. doi:10.3817/0691088057. S2CID 146928641. , p68

- ^ Hopkins, Kara (2006-04-24) Room of Her Own, The American Conservative

- ^ Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women, p. 281

- ^ Christopher Lasch: The Minimal Self. W.W. Norton & Company: New York and London, p.170

- ^ Christopher Lasch: Women and the Common Life. West.West. Norton & Company: New York and London, p.116

- ^ Deneen, Patrick (August ane, 2010) When Ruddy States Get Blueish Archived September 13, 2012, at archive.today, The American Conservative

- ^ "The treachery of the lites Elite sense of irresponsibility". March 10, 1995.

Further reading [edit]

- Anderson, Kenneth. "Heartless World Revisited: Christopher Lasch'southward Parting Polemic Against the New Class," The Good Society, Vol. six, No. 1, Winter 1996.

- Bacevich, Andrew J. "Family Man: Christopher Lasch and the Populist Imperative,"[usurped!] World Affairs, May/June 2010.

- Bartee, Seth J. "Christopher Lasch, Bourgeois?," The University Bookman, Jump 2012.

- Beer. Jeremy. "On Christopher Lasch," Modernistic Age, Fall 2005, Vol. 47 Effect 4, pp. 330–343

- Beer. Jeremy. "The Radical Lasch," The American Conservative, March 27, 2007.

- Birnbaum, Norman. "Gratitude and Forbearance: On Christopher Lasch," The Nation, October three, 2011.

- Bratt, James D. "The Legacy of Christopher Lasch," Books & Culture, 2012.

- Dark-brown, David S. "Christopher Lasch, Populist Prophet," The American Bourgeois, August 12, 2010.

- Deneen, Patrick J. "Christopher Lasch and the Limits of Hope," Start Things, December 2004.

- Elshtain, Jean Bethke. "The Life and Work of Christopher Lasch: An American Story," Salmagundi, No. 106/107, Leap - Summer 1995.

- Fisher, Berenice Thousand. "The Wise Onetime Men and the New Women: Christopher Lasch Besieged," History of Instruction Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 1, Women'due south Influence on Didactics, Spring, 1979.

- Flores, Juan. "Reinstating Popular Culture: Responses to Christopher Lasch," Social Text, No. 12, Fall, 1985.

- Hartman, Andrew. "Christopher Lasch: Critic of Liberalism, Historian of Its Discontents," Rethinking History, Dec 2009, Vol. 13 Upshot iv, pp. 499–519

- Kimball, Roger. "The Disaffected Populist: Christopher Lasch on Progress," The New Criterion, March 1991.

- Kimball, Roger. "Christopher Lasch vs. the Elites," The New Criterion, April 1995.

- Mattson, Kevin. "The Historian As a Social Critic: Christopher Lasch and the Uses of History," History Teacher, May 2003, Vol. 36 Issue 3, pp. 375–96

- Mattson, Kevin. "Christopher Lasch and the Possibilities of Chastened Liberalism," Polity, Vol. 36, No. 3, Apr. 2004.

- Miller, Eric. Hope in a Handful Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch Archived March 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2010.

- Nieli, Russell. "Social Conservatives of the Left: James Lincoln Collier, Christopher Lasch, and Daniel Bell," Archived August vii, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The Political Science Reviewer, Vol. XXII, 1993.

- Parsons, Adam. "Christopher Lasch, Radical Orthodoxy & the Modern Collapse of the Self," Archived December 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine New Oxford Review, November 2008.

- Rosen, Christine. "The Overpraised American: Christopher Lasch'southward The Culture of Narcissism Revisited," Policy Review, Nº. 133, October ane, 2005.

- Salyer, Jerry D. "Christopher Lasch: 1 of Bannon's Favorite Authors," Crisis Magazine September 19, 2017.

- Shapiro, Herbert. "Lasch on Radicalism: The Trouble of Lincoln Steffens," The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Vol. 60, No. ane, January. 1969.

- Scialabba, George. "'No, in thunder!': Christopher Lasch and the Spirit of the Age," Agni, No. 34, 1991.

- Seaton, James. "The Gift of Christopher Lasch," First Things, Vol. XLV, August/September 1994.

- Siegel, Fred. "The Agony of Christopher Lasch," Reviews in American History, Vol. 8, No. 3, Sep. 1980.

- Westbrook, Robert B. "Christopher Lasch, The New Radicalism, and the Vocation of Intellectuals," Reviews in American History, Volume 23, Number 1, March 1995.

External links [edit]

- Obituary: The New York Times, The Independent.

- Writings of Christopher Lasch: The New York Review of Books

- The Pursuit of Progress, 1991 interview on Richard Heffner's The Open up Mind: on the Daily Move; on Youtube.

- The Writings of Christopher Lasch: A Bibliography-in-Progress / Compiled by Robert Cummings (terminal updated 2003)

- On the Moral Vision of Democracy: A Conversation with Christopher Lasch

- Voices Against Progress: What I Learned from Genovese, Lasch, and Bradford, by Paul Gottfried

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Lasch

0 Response to "Family Is a Haven in a Heartless World"

Post a Comment